July 16, 2013

San Pedro de Abanto I: The weeks leading up to

the battle.

On 27 February 1874, Antonio López departed on a

special train from Granada to join the Army Operations North. My

great-great-grandfather was twenty years old and the military life was his only

path to prosperity. His departure from his home, a village on the plain of

Granada, coincided with bad news from the northern front. General Morriones and

the twenty-five thousand strong Liberal army, tasked with lifting the Carlist

siege of Bilbao, had been repulsed after two days of fighting. The Liberals

suffered over a thousand killed and countless wounded.

|

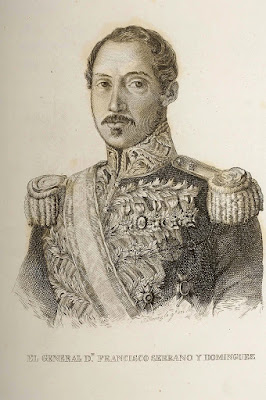

| General Domingo Morriones |

Morriones, aware of the impossibility of the

endeavor, had just sent a telegram: "Unable to break the enemy's line.

Send reinforcements and another commander." In Madrid, the telegram

produced an enormous uneasiness. General Serrano decided to resign the

Presidency to take charge of the military operations. At that time, the civil

war had lasted two years and its outcome remained uncertain. The Carlists

continued to besiege Bilbao and tried to conquer it, despite the impossibility

of their goal. Taking Bilbao was an old Carlist obsession; they had already

tried it during the First Carlist War. Now, just as before, the Carlists sought

to access Bilbao’s resources and obtain a success that legitimized Don Carlos’

claim to the throne in front of international powers. The pretender refused to

accept the first republican government in Spanish history, which had been

established after the abdication of Amadeus of Savoy.

Antonio had not forgotten the moment of his

enlistment in the army, just two weeks earlier: exactly a year after the

foundation of the Republic. Hounded and already mortally wounded, the Republic

would limp on another ten months before finally expiring. The desperate

financial situation—an enormous budget deficit and large payments immediately

due to creditors—and the ensuing political instability had led to rising

unemployment, hunger and unrest in the countryside. Benito Perez Galdos

described the situation in his National Episodes: "the ungodly

civil war, nefarious monster that showed me only her painful limbs. Two armies,

two military families, equally impassioned and heroic, tore themselves apart

for a throne and an altar. It would be difficult to say which of the two aged

furnishings was more severely battered and bloodied by the fight. In the annals

of world history, quarrels and a race’s pursuit of an ideal appear noble.

Conflicts as vain and stupid as Spain saw and withstood during the nineteenth

century, justified by illusory familial inheritance rights and scraps of a

Constitution, ought appear only in the history of cockfights.”

After

five days’ travel by train, Antonio arrived in Santander. The city had been

converted into a huge military camp, where reinforcements mingled with those

wounded in the previous battle. Four days later, on March 7, Antonio departed

for the front lines at Santoña.

The cover of the contemporary edition of Spanish

and American Illustration amply demonstrates the national crisis which

Spain was enduring. The caption reads: "We would prefer to introduce this

magazine by announcing a great and fortunate event of those which the country

has been awaiting with growing anxiety [...] we will have to delay a few days.

Impatience devours us in anticipation of upcoming developments that will free

our country from a harrowing and fratricidal war.”

Antonio was one of twenty thousand men that

Serrano had under his command. Their regiment, the Eighth Infantry of Zamora, 2nd

Battalion, was part of the Colonel Fajardo’s 1st Brigade, which was

encompassed in the 1st Division commanded by General Andía, which in

turn formed, along with sixteen battalions, the 2nd Corps of Field

Marshal Primo de Rivera.

The aftermath of the previous defeat was

immediately apparent to the soldiers. The rest of the country could get an

impression through the drawings published in Spanish and American

Illustration. One image of a field hospital was described as follows:

"It was necessary to convert the parish church of Somorrostro into a vast

field hospital, whose atmosphere stamped a profound impression of grief and

bitterness into the soul. There was a dreadful muddle between objects of

worship and those belonging to the Military Health Service. The pavement was

covered with straw and crowded with mattresses that had been commandeered from

the population. In them lay those unfortunate enough to have been more or less

severely wounded. Some complained plaintively, others shouted desperately, no

few were already immobile, with blank stares."

Field hospital at Somorrostro, drawn by José Luis Pellicer for the March 22, 1874 edition of Spanisand American Illustration

The

magazine also included an explosion which had occurred a few days earlier in

front of the Church of St. John: "Suddenly a vivid flash outshined daylight

for a moment, and a horrible sound reverberated. One of the aforementioned

wagons was filled with two large drawers of powder and no small amount of

loaded fuses and detonators. It had burst into flames, causing a horrific

explosion. Overcome by panic, the soldiers fled. Alas, many unfortunates fell

victim of this unexpected event, which was of the magnitude of a true

catastrophe.”

However, the battle had not even started, and the

worst was yet to come.

English translation by Katya Anderson of the spanish text:

dormidasenelcajondelolvido by José María Velasco is licensed under a Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 3.0 España License.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario